By Mekdelawit Deribe and Sukru Esin

July 2020

In the last 30 years a quiet but far-reaching revolution in our diets has occurred. Globally we eat more vegetables and fruit. Consumption has increased globally although not uniformly and sufficiently. This is a positive trend as WHO attributes 3-5 million deaths a year to diseases related to inadequate fruits and vegetable consumption. The observed trend, apart from the considerable effect on health and nutrition, has also created a high value sector in the hands of small producers, especially near main urban markets.

Increased demand for vegetables and fruits has resulted in increase in demand of seedlings. Soil conditions are not always optimal for seed sowing and hence seed loss is a common problem. In addition, due to heavy rains, insects and cold weather not all seeds can germinate equally. This is a challenge for a homogenous plant growth. The use of seedlings can alleviate all these issues and also create market opportunity for small holder seedling farmers.

Starting seeds indoors gives crops more time to mature within the growing season. This is critical especially in cooler climate or when working with slow growing plants. Using seedlings results in best results in places where temperature fluctuates quickly. With seedling production, farmer will also use less seeds. Farmer can grow more than one crop in a year with seedlings. Seedlings can also solve damage of seeds by rain, insects and cold weather and ensure homogenous growth, contributing to increased yield.

Both farmers buying and selling seedlings benefit from the use of seedlings. It’s not always possible for the farmers to have empty space for seedling growth. Especially farmers who have large scale lands and intensive cultivation, do not have enough space to grow seedlings. Therefore, buying seedlings is a good alternative for them, opening market for small holder farmers who can cultivate and sell their seedlings. Seedling farmer can also increase their profit by using recycled seed.

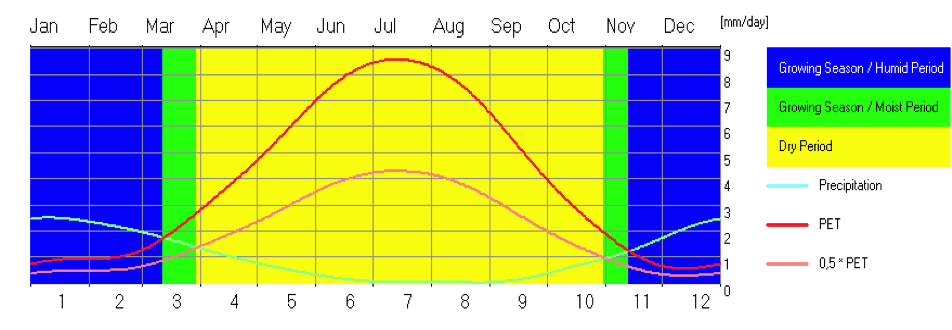

There is a great opportunity for the seedling market, especially in peri urban areas near main urban market places. However, there are also risks involved. Harvesting of seeds needs to start earlier than seed sowing. This requires knowledge of area specific planting calendars for different crops. Growing seedlings also take time. For at least 4 weeks farmers have to take care of the infant plants. This period can be up to 8 weeks. In addition, the seedling market is not yet established in many developing regions. However, low cost, small scale seedling schemes such as low and high tunnel greenhouses and production units can create jobs, increase yields and enhance economic benefits of farmer all around.